Will Bennett

See Exhibitions

Temporary Visitor for The Bush Points Back

Fluorescent tones of orange, green and yellow propel themselves from the painted surface of artist Will Bennett’s (Pākehā) otherworldly paintings that make up The Bush Points Back. Oil stick merges with deeply layered oil paint, creating a vehicle, or portal, from our world into theirs, and from their origin to the almost-apocalyptic world they temporarily inhabit.

Although these fun, playful, highlighter-bright colours could scream silly, things have suddenly got rather serious in Bennett’s latest series. We are watching a scene unfold in which the central figure is not at home. Instead, they are a temporary visitor. Bennett explores the feeling of disconnection to land and place, and when you have no link to the land you may trace ancestry back to.

Bennett’s love for references, especially art history, is clear in The Bush Points Back. He draws inspiration from both global art histories and the distinct New Zealand gothic. The artist continues his interest in rituals and ceremonies, and traditions that are practised by those who don’t have ownership over them.

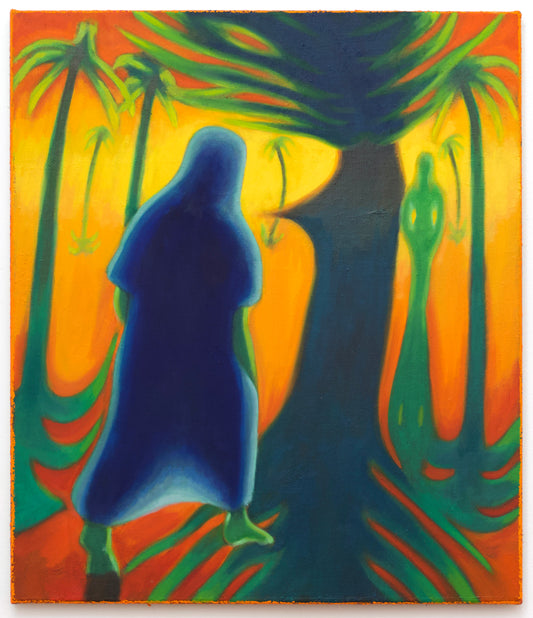

In works such as They warm themselves below Taranaki Maunga and Glowing pines, they warn the rabbit hunter, we see additional people in the background. These people, whether intentional or not, act as reminders to us of the landowners, or those who have more authority or presence over the landscape. They are often painted in the same colours as the landscape and remind us that the central figure is a temporary presence in the scene we are being shown. Are the background figures the true owners, and are they here to warn or remind us? Unlike those in the background, the central person, the temporary visitor, is often in blue or green, hooded, and is presented as an alien in the landscape.

The figure in Effigy for an ancestor wears a stylised version of a Waterloo Helmet, a pre-Roman, Celtic ceremonial helmet that was found in 1868 in the River Thames. This could depict Bennett’s own relationship to landscape and identity. His ancestors are Celtic, from the United Kingdom, but his family has lived in Aotearoa for generations and he was raised in Taranaki, yet he doesn’t specifically identify with either landscape.

Bennett’s title is curious: The Bush Points Back. Various paintings in the exhibition include gestures of hands and fingers. Certainly the title’s namesake, The bush points back, and A shaft of light include hand gestures as the main focus, with the green hands glowing from behind as if a torch is being shone through them or they’re being x-rayed. Bush wackers is a goofy, fake-horror take on ghosts using their hands to create a stereotypical ‘freaky’ impression of the Bogeyman coming to get you.

In Effigy of an ancestor the figure upon the horse points upwards. We look up. There is nothing - or is there? This is a familiar gesture, and Bennett again references traditions in art, such as Leonardo da Vinci’s Saint John the Baptist, The Death of Socrates by Jacques Louis David, and in Raphael’s The School of Athens a renaissance Plato is included pointing upwards. The pointed finger is often considered to allude to a higher, divine being - a god. Bennett’s The Bush Points Back almost alludes to Michelangelo’s creation scene of Adam. Does Bennett’s title allude to the figures pointing at the bush and the bush returning the gesture, asking who the higher being is? This ties into underlying questions about the relationship between landscape and people, ownership and authenticity.

The question of who is divine, or god, in Bennett’s world comes to the forefront in Pig-God. Introduced species, like boars and pine trees, have become familiar to New Zealanders. Bennett plays with these motifs and also incorporates the popular rural pastime of hunting.

Popular in Taranaki, Bennett includes nods to hunting with the insertion of the boar in his work, for example in Pig-God. The boar is popular prey for hunters, and throughout history has also been seen as being sent by a higher being (whoever Effigy of an ancestor is pointing to?), to punish the human race. In Celtic cultures, boars not only symbolised punishment, but also strength and transformation, otherworldly activity, good health and fertility. The creatures’ highly symbolic nature play into Bennett’s paintings containing the animal. In the Roman world the wealthy had specific boar parks for hunting, called vivaria, where boars were lured to come running when they heard music, and then were hunted in short range, providing excitement for both hunter and guest alike. Maybe Pig-God is a reference to the cruel, but sometimes necessary reality of the pastime, and a hint to hunting spanning many cultures and centuries, not only today’s. The triangular ultramarine blue portal, one of Bennett’s icons, is in the background of the painting, flanked by trees. In Pig-God, the boar is given pride of place.

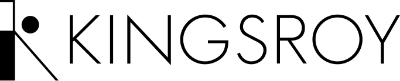

This body of work, fittingly, also speaks to Bennett’s own upbringing within the Taranaki landscape. In They warm themselves below Taranaki Maunga, Taranaki sits in pride of place with the moon shining upon it. A central hooded figure sits warming himself by the fire beside, presumably his, Cane Corse. Background faceless figures walk along, gazing at either the maunga and the moon or the man and his dog.

Along with faces, emotion enters. We feel the despair, grief and longing of the character in Twisted limbs, fallen leaves, they weep in its shadow, head in hands, hair flowing over face. Bennett grapples with the idea that when we spend time in nature, surrounded by landscapes in all their forms, they can affect our feelings and emotions. However when we are sad, happy, and everything in-between, we have no effect on the landscape in return. Bennett’s paintings depict how the landscape might look if it was affected by human emotions.

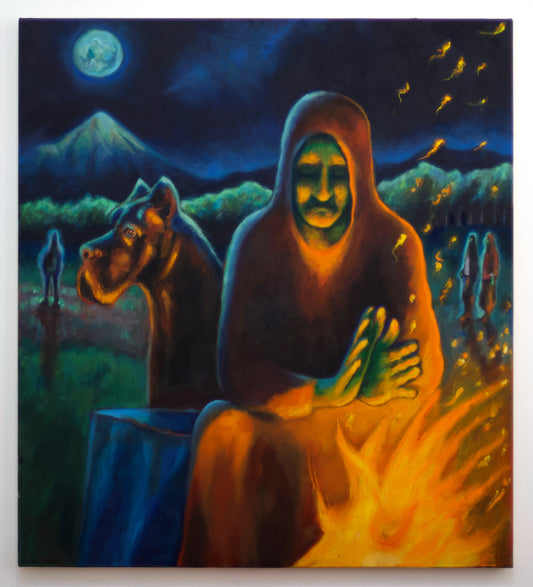

We end on an uplifting note in A Step Towards. The hooded figure walks towards a figure that is one with the landscape, carved out of the shape and colour of the palm tree trunks around her, glowing from behind is a luminous gold-yellow that is more positive than the alerting orange and red. The figure is taking a step towards the landscape and those that are part of it, towards love, towards something positive, perhaps towards a landscape that feels a little more his own.

\ Lucy Jackson